Suncatcher by Romesh Gunesekera review – coming of age in Sri Lanka - The Guardian

Suncatcher by Romesh Gunesekera review – coming of age in Sri Lanka - The Guardian |

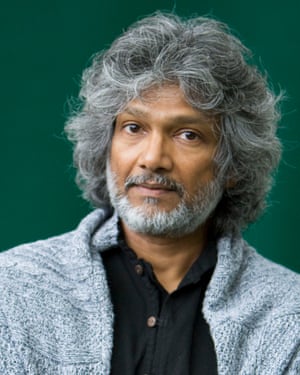

| Suncatcher by Romesh Gunesekera review – coming of age in Sri Lanka - The Guardian Posted: 06 Dec 2019 12:00 AM PST Kairo is growing up in 1960s Sri Lanka at a moment of gathering political repression and destabilising social change. His father is a dyed-in-the-wool communist, in an armchair sort of way. His mother is trying to work out what to do about her son's education now the schools have been suspended. But Kairo doesn't care too much about all this. He's just met Jay – be warned, it's never a coincidence when the glamorous, wealthy character with the gilded life is called Jay – and he's going to appear in a coming of age tale. Jay has a life that Kairo finds intoxicating. His family are rich and live in a beautiful house; he has an attractive, unstable mother and a gangsterish uncle with a farm and a classic car collection; he likes to cycle, drive, shoot, build, skinny-dip, defend the helpless and all the other things boyhood heroes do. His bedroom is filled with metaphors for the contained experience of childhood – fish tanks, in this case, which also give us a hint of Jay's possible fetish for control – but Jay and Kairo are growing up, and need a new, more apt metaphor for the half-freedom of adolescence. So they build a cage for Jay's budgies, where Jay also keeps a sutikka, a bird native to Sri Lanka that he's caught, which he calls his "Sunbeam". The title of Romesh Gunesekera's novel invites us to draw parallels between this bird and Jay. And if you haven't worked out how the book ends already from the character's name, you'll have a second opportunity to see the story's destination heavily foreshadowed in the fate of the bird. A series of metaphors for the dangers waiting in the adult world assail the cage Jay and Kairo build – a monitor lizard, some crows – and when the boys go away for a weekend at Jay's uncle's farm, we begin to see how these dangers can assail them in the real world. Jay's urge to control comes up again, and we're asked to question his attitude towards all these things he cages when something really gruesome happens to a local farm boy whom Jay treats as part friend, part moving target. This harrowing incident, the most successful passage in the novel, appears and disappears without particularly affecting the plot, besides providing a metaphor for the way the rich treat the poor in Sri Lanka. The book carries on to its inevitable conclusion, one family falling apart, the other not seeming so tawdry after all, a schematic romance subplot being sketched in and the cage metaphor coming up again and again.  Gunesekera is an internationally acclaimed writer with a significant body of work, but his new novel is a programmatic piece of genre fiction, the coming-of-age storyline that launched a thousand films. An interesting sociopolitical setting is offered up but sketched so lightly that it doesn't feel as though the book would need to change more than a few nouns in order to move to Australia, America or anywhere, really. This is partly because Kairo is an intentionally naive narrator – there's a funny moment where he confuses "aviaries" with "ovaries" – but elsewhere, characters' digressions on the theme of communism read like pub chat, interchangeable with any other political hot topic. The writing is sometimes clumsy – what does "he relied on a comfortable compromise between idealism and action which now, with socialism back in the fray, was beginning to show some strain" mean? Why can't socialism accommodate both idealism and action? Should "action" perhaps be "pragmatism"? Has anyone ever really said "Beauty needs appreciation, and the adoration of the young is a wonderful thing" when talking about going for a drive in a car? Why has a sentence like "a fishing trip involved more deliberate deaths, and this time I would be the one doing it" not been sharpened up? It's not possible to "do'deliberate deaths: they're not a verb. And when a Bible falls open, entirely by chance, at the most apposite possible verse (Proverbs 30:17), I despair. A writer just can't be this paint-by-numbers and invite comparisons with F Scott Fitzgerald. Glimpses of a lyrical and soulful voice flicker occasionally – Gunesekera touches universality when he writes "I was convinced that we were more than what we seemed: that we were boys whose bodies were dross, whose bodies would one day be discarded". Ultimately, though, Suncatcher gives off the strangest air of not actually being a novel. It's the plot of a teen movie reheated, all detail planed away to make room for the conventions of genre. It makes one ask what stories are actually for – aren't novels called novels because they should contain something new? • Barney Norris's latest book is The Vanishing Hours (Doubleday). Suncatcher is published by Bloomsbury (RRP £16.99). To order a copy go to guardianbookshop.com. Free UK p&p over £15. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "beautiful fish tanks" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment