A tiny fish is on the brink of extinction. Does it matter that another just like it is thriving? - WHYY

A tiny fish is on the brink of extinction. Does it matter that another just like it is thriving? - WHYY |

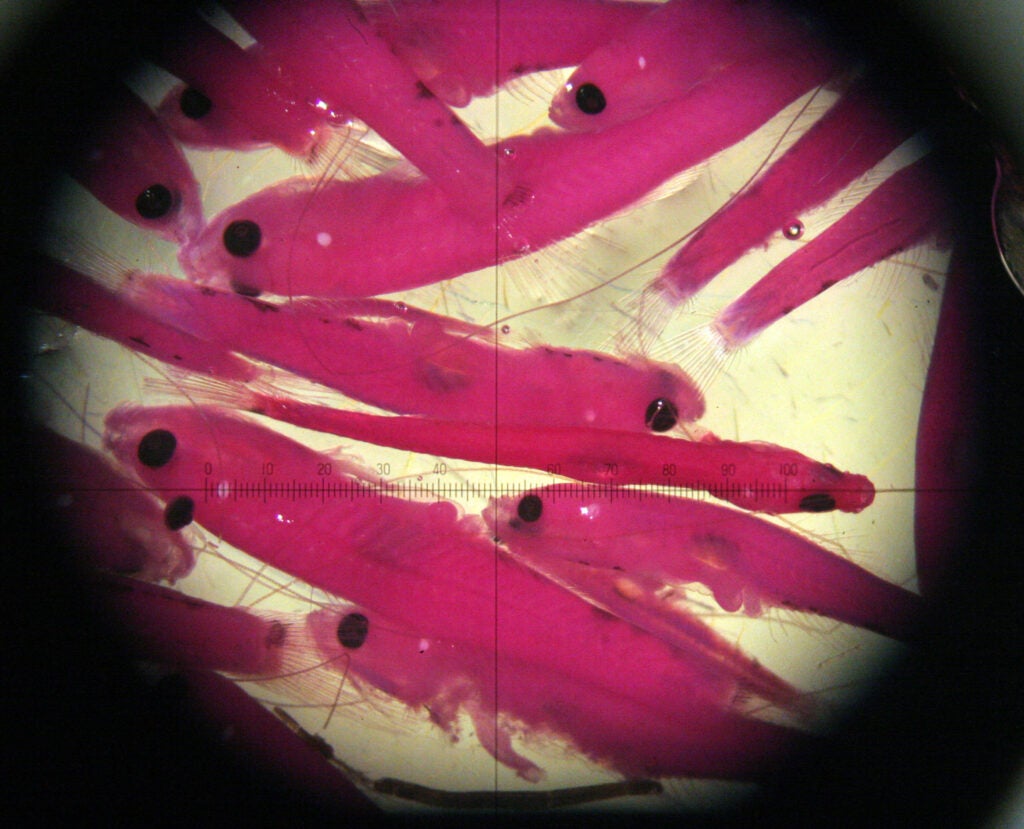

| Posted: 26 Feb 2021 03:02 AM PST This story is from The Pulse, a weekly health and science podcast. Subscribe on Apple Podcasts, Spotify or wherever you get your podcasts. California's tiny delta smelt is not a terribly impressive fish at first glance, and not really at second glance either. It's about the length and width of a finger, silvery and kind of see-through – looks a bit like a sardine.  They're not particularly clever or cute, but Mandi Finger, a University of California Davis population geneticist, says the delta smelt do have one weird characteristic going for them. "They smell amazing," she said. "They smell like the best version of cucumbers you could ever imagine." No one knows why, not for certain. "I know they smell great though. They really do," Finger said. "I've gotten to smell a delta smelt, you know, before they were all gone." Every year, scientists go out in search of these fish, scouring the tangles of streams and wetland in northern California's Sacramento-San Joaquin River delta. They've been finding fewer and fewer for decades, only catching a handful in the past few years.  It looked like they weren't going to find any this most recent season. That is, until just before an interview with Finger in January. They found a single fish and dropped everything to get it back to tanks alive with other smelt that scientists are raising in captivity at the University of California Davis Fish Conservation and Culture Laboratory. "There's black tanks with filtration systems and, you know, with shade cloth over it, and a couple of trailers," Finger said. "So it's pretty small. Like you would never know that's where all the delta smelt in the world are." Technically, it's only half of the remaining delta smelt. A backup site near Mount Shasta has other refugee delta smelt in case fire or earthquake or something knocks out Finger's refuge. She's been working with these fish for 10 years. "I basically am a matchmaker for delta smelt. The hatchery personnel put tiny tags with individual IDs into the males and the females, and then we do the genetic analysis on the fish," Finger said. "And I tell them specifically, 'Mate Y-O 33 with O-W 67.' And I do that based on relatedness. I'm trying to minimize relatedness so that they don't become inbred." She's trying to buy time. Eventually, the idea is to release these fish into the wild again. But in conservation, it's not enough, apparently, to just keep certain numbers of a threatened fish alive somewhere safe and secure. "A delta smelt in a hatchery is a hatchery smelt, not a delta smelt," Finger said. "Every species is shaped by their environment. They [start to] get shaped by a hatchery environment." Finger's fish refuge started with fish caught in the wild in 2006, and with each passing generation born and raised in the tanks, they've started adapting to that environment. Genetically speaking, they become less and less wild. Traits that serve artificial tank living over natural delta living increasingly win out. "You can slow it down, but you can't stop it," Finger said. Slowing it down used to be easier when scientists were catching more wild delta smelt. Finger had all these wild young single fish to throw into the tank mix. They'd spread their wild genetics around. Those days are gone.  'Every individual is precious'Now, one single wild fish is a show-stopper. "But it's just like, oh my God, you know, one fish is not enough," she said. "I mean that's coming from a population geneticist who doesn't believe that individuals are that special." Earlier in the interview, Finger had referred to individual animals as "little sacks of DNA." Small potatoes in her field. "But now, we're down to that level, which I hate to be in, where it's like, oh my God, every individual is precious," she said. Without introducing enough wild delta smelt, tank-raised smelt will eventually become something akin to a different species. That's a problem because, in conservation, species is everything. Finger and others have done research that found scientists were having a hard time telling delta smelt apart from a fish species from Japan called wakasagi. "You know, when you have them in your hand and they're small or they're in a bottle and they've been jostled around, it's hard to identify them," Finger said. Wakasagi were introduced by the government in the 1950s. There's no shortage of them here or in Japan. Especially when they're young, to the naked eye they look virtually identical to deltas. They're so similar, in fact, to the nearly extinct fish that scientists were worried about hybridization — that this plentiful species and the delta smelt would start hooking up, making mixed-species fish babies.  At some point, scientists worried wakasagi-delta smelt hybrids would eventually be more wakasagi than delta smelt, and therefore no longer endangered but also — in a way — extinct. Once a species hybridizes with another, you can't unscramble that egg — the original species is lost. With delta smelt and wakasagi, that didn't end up happening. But why not just let it happen? Why not maybe encourage it? Wouldn't some small part of the delta smelt still live on in future wakasagi hybrids? "We're in such dire shape with delta smelt that you want to think outside the box, you know?" Finger said. "OK, so wakasagi obviously is doing a lot better. Should we consider, you know, interbreeding wakasagi and delta smelt to make them more fit in the ecosystem? Because the ecosystem is not supporting delta smelt. That is clear." The answer, at least for now, is definitely no, she said. It would be like giving up on the delta smelt to let this distinct species melt into something else. It makes you think though: Why go to so much trouble to preserve so many species, to preserve this one particular cucumber-smelling, sardine-looking species if there's another one essentially just like it? "It's funny because I had a lot of conversations about this over the last few days, because I knew you were going to ask about it," Finger said. "And first of all, I think as a society, you know, we passed the Endangered Species Act to protect species, and the delta smelt is a species. And if it goes extinct, we've lost something that we can never recover. So it falls in line with my personal ethics that I think it deserves to exist because it does exist." It's a beautiful sentiment, really. But part of what makes the question "Why bother?" so complicated is that there's so much stacked against the delta smelt. So many competing, human interests. For such a small fish, it has a lot of enemies. No smoking gunIn California, the delta smelt is a major player in the state's water wars as environmentalists and farmers and developers all jockey for scarce water-use rights. Biologist Peter Moyle is perhaps one of the delta smelt's oldest and most loyal allies. "Now, one of my great regrets was that when I was working with smelt and they were abundant, I never ate any of them," he said. Decades ago, when he first asked for delta smelt to be delivered to his lab, there was a truckload of them. "This truck pulls up to the building, and they said, `Where do you want all these smelt? It was literally a truck full of boxes of smelt," Moyle said. "I just remember being incredibly impressed by how many fish we have." Moyle first noticed the delta smelt's decline, in the 1980s. The story of how it got so near the edge tells a lot about why it's so hard to keep the smelt from falling off. "You have to realize that the delta is the heart of California's water system — literally, the beating heart of California's water system," he said. The smelt's decline tracks with water being pulled out of the system, that's the biggest factor, Moyle thinks. "The problem is there's no smoking gun," Moyle said. "Because every year there's also other things going on." For example, he says, in the1980s, "There was the invasion of small clam, the overbite clam." The clam came from ballast water from huge cargo ships and ended up making the water super clear by filter feeding, which is harmful to delta smelt hiding from predators. It's just one example, but Moyle's point is there are always new factors — human and animal, increasingly climate-related, that come in and complicate things for the delta smelt. The thing is, these fish evolved to be survivors. They live only one year, which means an extremely dry year or an extremely cold year can threaten the entire species. So delta smelt improvise — they use what scientists call multiple life history strategies. "Which simply means that in different years, smelt were doing different things so some portion of that population was always doing the right thing," he said. Some would spawn in different areas or swim at different areas of the water column. Some would even live two years instead of one. But even that ability can't save the delta smelt, not these days. "It's pretty remarkable that we screwed up the estuary to a point where none of those strategies would work anymore," Moyle said. The delta smelt became the "face," so to speak, of a big fight over water and who needs it more. A fight over what matters, and why it matters. Conservation efforts end up being a push and pull. In a way, saving the delta ecosystem or at least trying to is a bit like drawing a line in the sand: This is exactly how bad we'll let this patch of the earth get — to where it can still support this little fish — and hopefully that means some of its buddies in the animal kingdom get a chance to survive too. Maybe we get a chance. "This is a wicked, wicked problem, as they say, there's no really one good solution," Moyle said. "But if you can use the delta smelt as the reason you clean up pesticides, for example, there's a lot of the nasty chemicals that are still flowing into the delta. If it becomes a species which provides additional ammunition to clean up the water, this then obviously benefits humans as well."  Picking winners and losersThe delta smelt's habitat is being restored. Whether it will be restored quickly enough to support the refugee deltas Mandi Finger is watching over is anyone's guess. People interviewed for this story all brought up the Endangered Species Act. It's a powerful law that says animals have gone extinct because of us, because of human actions, and we need to put a stop to it. Thousands of species are around today that surely would have gone extinct without the law, but the big question for many conservationists is: Has the Endangered Species Act truly prevented those extinctions, or merely delayed them? What good are Finger's carefully matched tank-raised delta smelt if their delta home is never really safe? It's true that some animals face extinction because of over-hunting or poaching or some other, simple villain, but increasingly the picture is complex — a tangle of responsible factors driving species to the brink. Does trying to save every species still make sense? Is it even possible? Chris Thomas, director of the Leverhulme Centre for Anthropocene Biodiversity at the University of York in the United Kingdom, said the philosophy of saving every species comes from a pretty grim issue: There are animals that go extinct naturally — it's always been a part of life on earth. Then there are the animals human activity drives to extinction. The problem is, we can't tell which is which anymore. "Because human activities on the planet are so pervasive," Thomas said. "The greenhouse gases, the CO2 in the atmosphere, has changed photosynthesis of every plant individual on the planet." He spent a lifetime in the field, counting this plant or that, or butterfly eggs. He used to believe the "save everything" gospel. But not anymore, and he gave few reasons. "The first is that we'll fail, and there's not much point putting all of your efforts into what you know is not going to be successful on a timescale — let's say the next century," he said. A lot of this is driven by climate change. Thomas said it's possible a full three-quarters of all animal species are now on the move in some fashion because of the climate. More is changing than just the namesake Delta that the Delta smelt calls home — the entire planet is, all at once. "Well, it's just impossible to keep things as they are. The human population of the planet is still continuing to rise," Thomas said. He advocated a more dynamic kind of conservation, one that deliberately picks winners or losers. Which, he argued, we already do, even if we don't admit it. We care about noble gray wolves and cute pandas while countless snails and spiders so obscure as to only have Greek and Latin scientific names fade quietly into oblivion. Finger says an animal's existence is its right to exist. Thomas thinks that idea has more to do with us, with humans, than with the animals themselves. "I think that the articulation of an intrinsic value of nature is, in a sense, I wouldn't say it is religious, but it is akin to religious belief in the value of something that it has some kind of independent existence that is separated from the human," Thomas said. "And so when we value it, we are the people who are doing that valuing." Thomas respects that, but he thinks we have to be pickier. Tough choicesThere are two emerging strategies. The first is to preserve exceptionally unique species. New Zealand's tuatara lizard, for example, looks like any old iguana, but it's actually the last of its order — the sole heir of distinct genetics from 250 million-year-old ancestors. The other strategy involves preserving backup species, plants or animals that are important to us or larger ecosystems. If a certain utilitarian tree species goes extinct in Asia, maybe a similar enough one survives in South America. In short, Thomas said, we have to start making decisions, tough ones. There's too much at stake not to. "All future biological communities, all future ecosystems are going to be constructed from the descendants of today's species," Thomas said. It's more difficult, and perhaps even more hubristic in a way than the "preserve everything" ethos. How are the humans of 2021 to accurately guess what's going to be best for a future ecosystem we won't be around for? Both the tests that should help us decide — the uniqueness test and the backup for a useful species test — likely will fail the delta smelt. The delta ecosystem would hardly notice if the delta smelt completely disappeared. In a cruel natural irony, the more scarce an animal becomes, the less important it is for the function of its natural habitat. And likely most of us on land wouldn't notice, blissfully ignorant of a cucumber-y fish we never got to smell and never will. "I can't tell anybody who will never, ever even know that delta smelt existed – and, you know, they got their own problems – that they should feel this great loss because delta smelt is gone now," Finger said. "But I know that they are going extinct, and I know better." She said she has to remind herself sometimes that most people are not preoccupied with this tiny fish. "When I found out they hadn't caught any wild delta smelt this year, I called my adviser and I was almost in tears. I was like, what do I do? You know? And he's like, 'Well, some problems aren't solvable,'" she said. Finger, of course, just kept going to work. She emailed to say that researchers had recently found a second delta smelt, a female. She matched her with an eligible bachelor just after Valentine's Day. "It's the politics, and there's so many people in California, and it's just such a hard battle. And you know, you asked me, why do we preserve this fish? And you know, sometimes you're like, I don't know, like it's looking pretty grim," she said. "But on a day-to-day basis, they're still here." |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "beautiful fish tanks" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment