Patagonian paradise lost? The environmental hazards of farming fish in a warming world - Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists

Patagonian

paradise lost?

A salmon farm in Comau Fjord in 2021. (Photo: Alvaro Vidal)

Patagonian paradise lost?

The environmental hazards of farming fish in a warming world

By Jessica McKenzie

June 21, 2023

Daniel Casado, tall, bearded, and swathed in dark grays, met me at the tiny airport on Chiloé Island in his camper van. Casado, a photographer and documentarian, is one of the cofounders of Centinela Patagonia, a new organization dedicated to protecting the region's unique environment.

I had traveled to Chile to join the group on its first expedition to survey the impact of salmon farming in Los Lagos, where the salmon industry was concentrated for years and still maintains a significant presence.

Casado drove us out of the hills to Dalcahue, a quaint fishing town bustling with tourists on summer holiday.

We strolled down to the water to meet the other cofounders: Rafaela Landea, the group's president, Alessandro Bocconcelli, a gregarious Italian oceanographer emeritus from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, and Thomas Montt. Montt grew up in Dalcahue, where his father, Pepe Montt, runs a fish export business. Back in the 1980s, Pepe worked at a salmon hatchery, and later built pens for aquaculture companies.

They were busy preparing the Centinela, the boat Pepe loaned the group for the nine-day journey. Its name, which means sentinel, also inspired the group's name: Centinela Patagonia, or guardian of Patagonia.

The morning we set off dawned cool and overcast. The edges of the narrow channel were choked with aquaculture—sprawling mussel farms with line after line of buoys. We soon passed the first salmon farm. I peered out the window, trying to make sense of something I had only read about.

The farm consisted of a dozen or so square pens in two rows, each roughly 90 by 90 feet. They were covered with nets to keep out birds. At the edges of the floating structure—easily larger than a football field—a foot or two of underwater netting was visible. The pens are essentially submerged cages where young salmon, or smolts, are raised until harvest. As my eyes adjusted to the glare, I could see the silvery fish leaping out of the water.

The open weave of the nets allows water to move through, flushing the pens of excess food and salmon urine and feces. Although sea water should provide the salmon with enough oxygen, most farms also had rafts of oxygen tanks, which are used to increase the amount of dissolved oxygen in the pens. Bocconcelli pointed out the automatic feeders in each pen: narrow tubes spinning around, spitting out kibble-like fish food.

Critics describe these facilities as floating feed lots, but it can be hard to see the extent of that similarity at first, because the farms are mostly underwater, and most of the pollution they produce can't be seen from a boat. Montt drew my attention to plumes of oily water floating away from some of the farms. When we passed particularly scummy water, Bocconcelli took samples to send away for testing.

The farms were surrounded by floating buoys marking the anchors that attach the pens to the ocean floor. Sea lions often lounged on top, ignoring the spikes or barbed wire meant to deter them. Workers moved around on metal walkways, sometimes stopping to watch us. A few times someone at the farms would radio the boat to ask what we were doing, or pull out a phone to photograph us.

In Quellón, an essential port town for the salmon industry, boats heavy with fish came in, and boats hauling food and equipment departed. A newly constructed farm floated in shallow water, waiting to be towed out to sea. Long tubes ran from holding pens up the beach to processing facilities on shore. Some of the pens sagged into the water under the weight of accumulated kelp and shellfish.

We crossed the Corcovado Gulf to the mainland, the gulf's namesake volcano rising up to an iconic peak on the horizon, and went ashore on a remote beach. Although there wasn't a salmon farm in the immediate vicinity, it was littered with plastic detritus, carried there by the wind and waves.

Photos by Jessica McKenzie

In a statement, Intesal, the technological arm of the industry group SalmonChile, touted the "Comprometidos con el Mar" (or "Committed to the Sea") program launched four years ago, which has spearheaded several beach cleanups in southern Chile. The ultimate goal of the program is to reduce the amount of inorganic waste entering the environment. But from what we saw, plastic remains a challenge.

Photos by Jessica McKenzie

Seen from up close, the scale of the pollution was enormous. Where the beach met the rainforest, trash snagged on the large leaves of the understory. There was a shrub growing out of a buoy green with algae that looked, at first glance, like a rock. We followed a stream to a hidden waterfall tumbling over a mossy cliff; plastic litter formed an unnatural dam where the stream ran out to the ocean. Tiny globules of white Styrofoam swirled in the eddies.

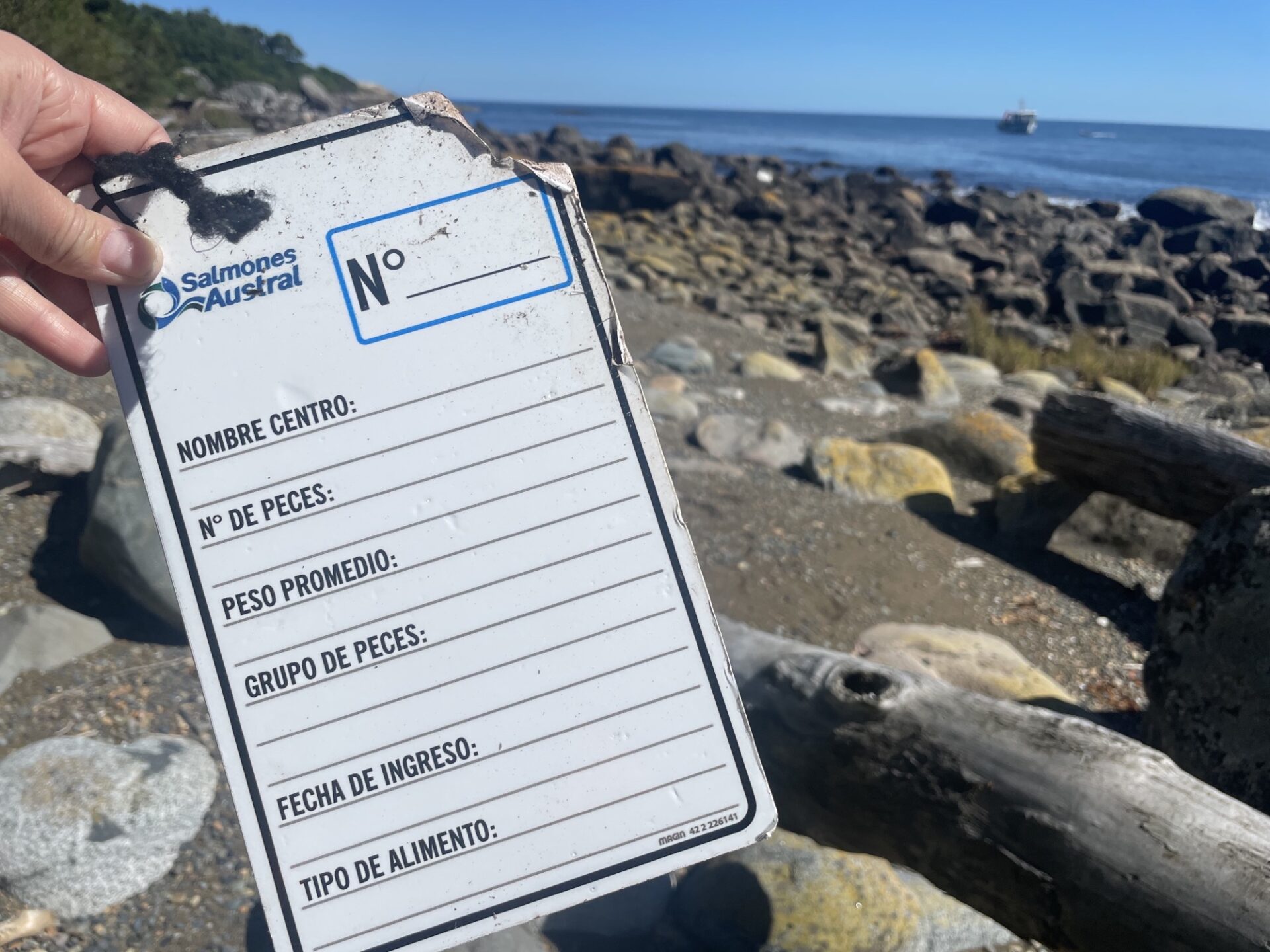

If there was any doubt as to the source, we also found an identification tag from a salmon farm. The beach was desolate, accessible only by boat—but that special human something was everywhere. And yet plastic is only the most obvious kind of aquaculture pollution.

Nobody ever asked Ana Leviñanco if she wanted a salmon farm in front of her home. One day they just came. That was almost 30 years ago.

Leviñanco lives with her husband on a sandy point on Caguach, in the Chiloé Archipelago. Landea, Casado, and I visited late in the morning, after she and her family had spent the early hours gathering luga, a kind of seaweed, at low tide. They sell it to companies that extract carrageenan, a common food thickener. It was spread out over their front yard, drying in the sun.

In 2007, the salmon farm visible from their living room window was one of many closed amid an outbreak of infectious salmon anemia, a highly contagious viral disease that swept through the Chilean salmon industry. The company, Marine Harvest, left behind a pontoon, some buoys, and a beach littered with trash, but kept the aquaculture concession. Last August, Marine Harvest returned, now operating under the name MOWI, and restarted the farm. (MOWI did not respond to a request for comment.)

Boats come and go at all hours. Lights and noisy generators run throughout the night. The high tide line is littered with bits of Styrofoam and other plastic waste mingled with shells and bits of seaweed. Leviñanco said the ocean foam is sometimes tinged pink and oily to the touch. Her family has stopped collecting luche, an edible seaweed, near the farm because it is awash in feces and chemicals. She and many of the island's other 480 residents worry that the local sea snails, clams, and mussels are no longer safe to eat.

Alex Mayne, a friend of the Leviñancos who sat in on our meeting, said that for centuries, the indigenous people of the Chiloé Archipelago built fishing corrals out of stone. Fish came at high tide to feed on algae and were trapped when the tide ran out. The corrals functioned as food storage in the years before refrigeration became common. Now, Mayne said, the fish don't come because the rocks are bare.

The amount of nitrogen released by Chilean salmon farms every day is comparable to the waste of 9 million people.

Leviñanco said she has no recourse against the salmon farms. "She feels very alone in this fight," Landea translated.

She has good reason to be concerned about the effluent from salmon farms. Researchers estimate the amount of nitrogen collectively released by Chilean salmon farms every day is comparable to the waste of 9 million people. To put that in perspective, Chile's total population is just over 19 million people.

When she lived in the Aysen region, Landea went diving near a salmon farm and saw how food and feces accumulated below the nets in a "pyramid of shit."

Microbes thrive in that environment, feeding on the organic matter and using up the oxygen in the water. This can lead to hypoxic (too little oxygen) or anoxic (severely low oxygen) conditions on the sea floor, killing anything that requires oxygen to survive. Most studies have found that salmon farms have some level of eutrophication, or excessive nutrient loads that lead to oxygen depletion, beneath them. Sites in sheltered parts of the sea, with slower water currents, are especially susceptible.

A government report found that only a quarter of Chilean fish farms had anaerobic (no oxygen) conditions in the sediment beneath them in 2016. But waste from the farms could be causing problems elsewhere.

According to the University of Concepcion's Renato Quiñones, the lead author of a review of the scientific literature on Chilean salmon farming, the fate of nutrients introduced by salmon farming is poorly understood, particularly in deeper fjords where the floor of the ocean is too steep for the waste to accumulate directly below the farms. "All the organic and inorganic material goes somewhere," Quiñones and his colleagues wrote. "Although greater circulation could facilitate recycling, organic matter may also be accumulating in the deeper bottom of the fjords beyond the farms. Such impacts are not being examined or monitored."

Comments

Post a Comment