Shovelnose guitarfish: surviving in the sea for 100 million years - One Earth

Each Wednesday, One Earth's "Species of the Week" series highlights a relatively unknown and fascinating species to showcase the beauty, diversity, and remarkable characteristics of our shared planet Earth.

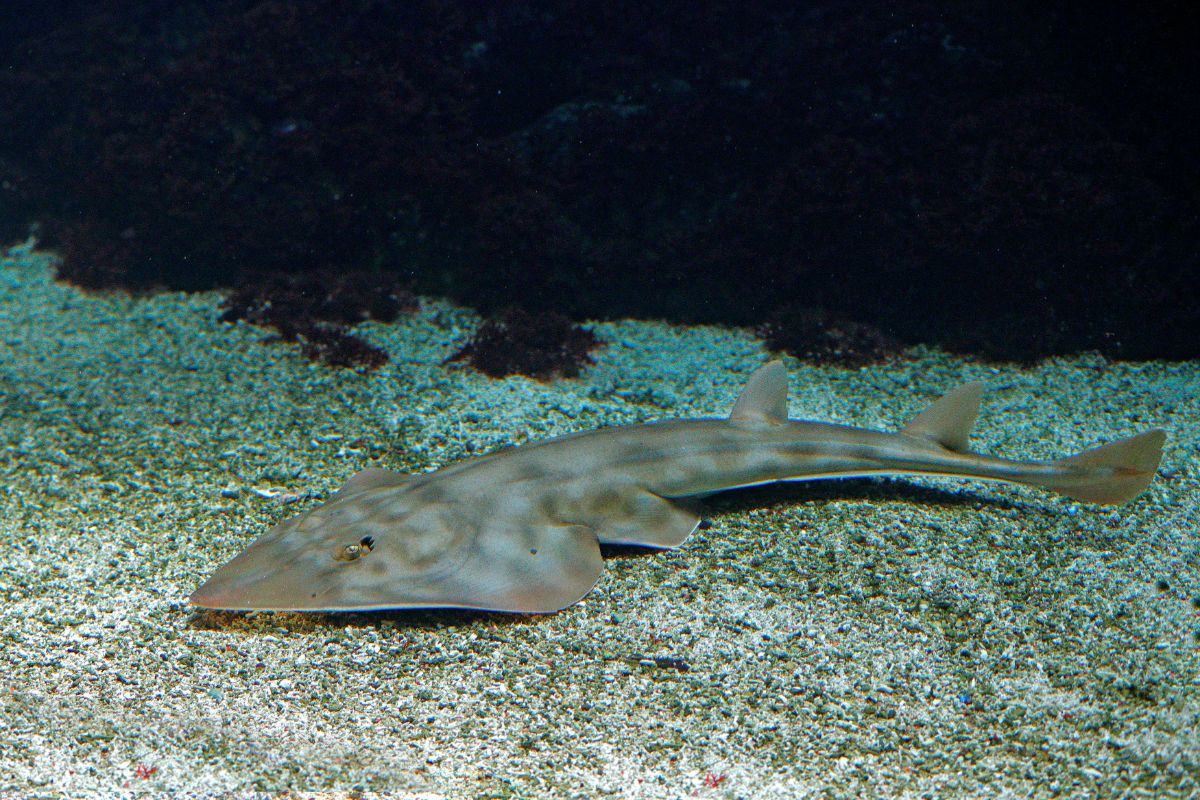

Stingray, or shark? Neither, actually, though Rhinobatos productus, or the shovel-nosed shark are related to both. The genus name — Rhinobatis — is a combination of the Greek word "rhine" meaning shark and the Latin word "batis" meaning ray. Recent studies confirm that guitarfishes are rays and are most closely related to the diverse group of skates. They look like sharks and swim using their shark-like tail rather than flipping their pectoral fins as most rays do.

Its common name is derived from its long, pointed snout and a guitar-shaped body. Its flat body is adapted to life on the sand - its olive to sandy brown tone help it blend into the sandy shallow seafloor where it lives its life, usually in less than 40 feet of water.

A guitarfish's mouth is located at the bottom of its shovel-shaped head, well-positioned for eating bottom dwelling prey that it lies in waiting for, buried under and camouflaged by inches of sand. When an unsuspecting crab or flatfish passes by, the sand suddenly erupts, and the guitarfish eats. At night, they leave the sand to hunt, dragging the seafloor for crabs, worms, clams and other fishes. They crunch crabs and other shelled invertebrates with their pebble-like teeth. Large, coastal sharks and California sea lions are their only known predators.

Shovelnose guitarfish. Image credit: Shutterstock

Like all sharks and rays, guitarfish reproduce via internal fertilization. Each embryo receives nutrition from a yolk sac, and females give birth to live, well-developed young. Immediately after birth, juveniles set out on their own.

Shovelnose guitarfish can be found from Central California to Baja and are numerous throughout their range. Yet, Shovelnose guitarfish are threatened by human activity, specifically by fisheries that capture them for human consumption, as well as by accidentally capture in net fisheries targeting other species. Their numbers have been depleted significantly, and are now listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN), as endangered.

This ancient ray has glided over sea floors for 100 million years. Close monitoring and conservation efforts can ensure that it is able to do so far into the future.

Comments

Post a Comment