A true fish tale: How a railroad crash boosted Nebraska's fishing stock in the late 1800s - Omaha World-Herald

A true fish tale: How a railroad crash boosted Nebraska's fishing stock in the late 1800s - Omaha World-Herald |

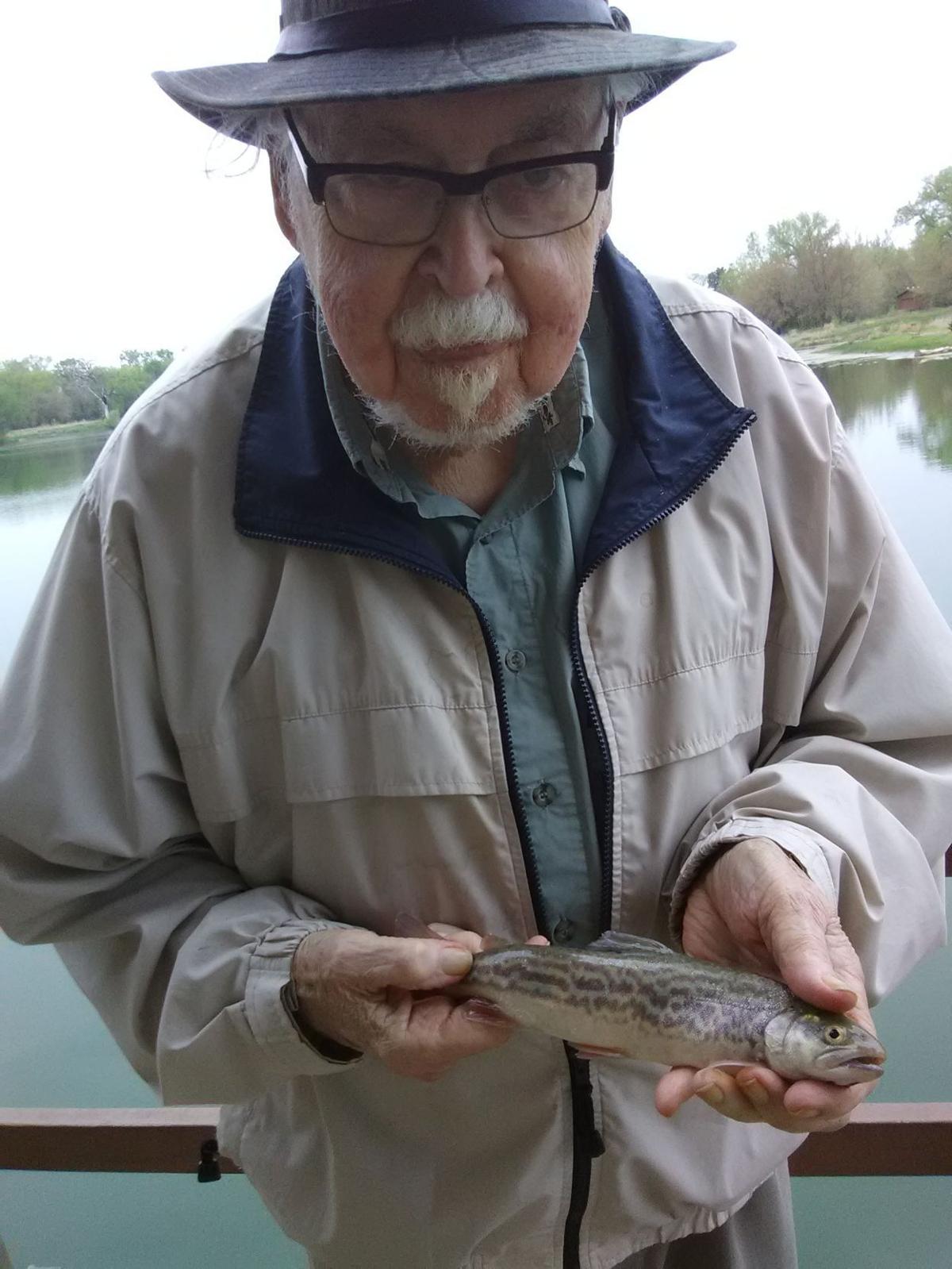

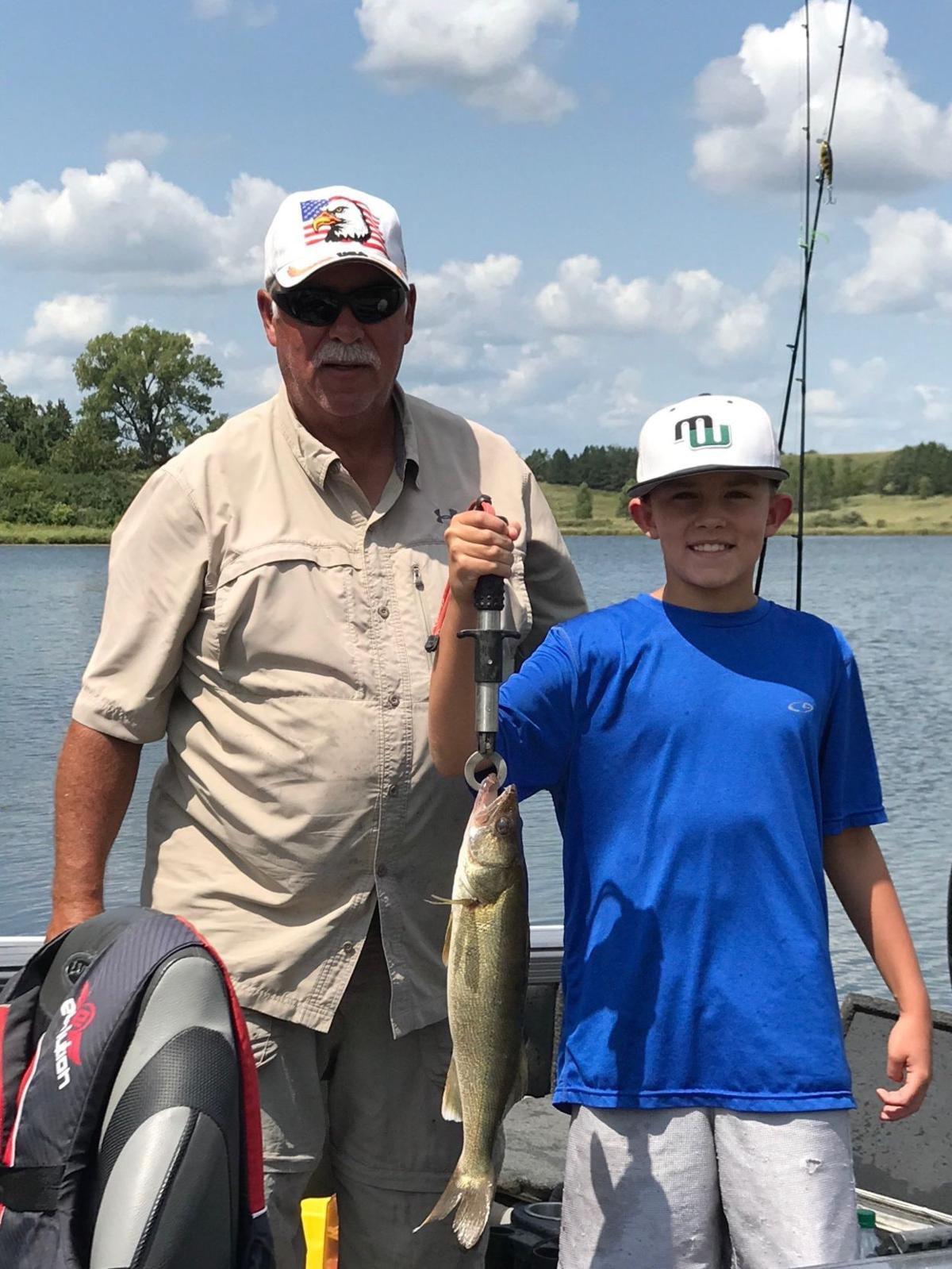

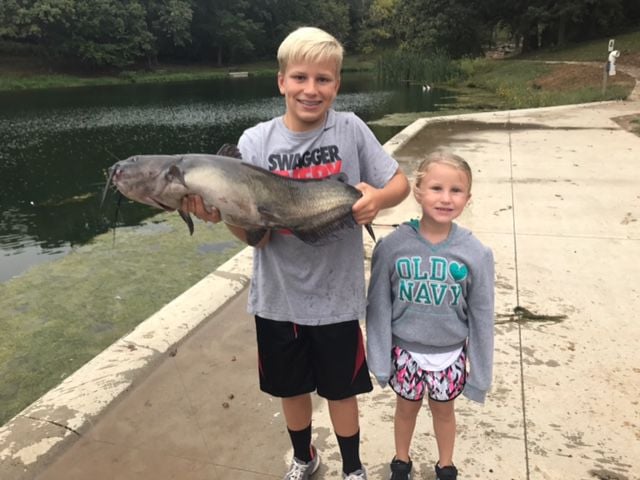

| Posted: 10 May 2020 12:00 AM PDT Salmon caught in the Platte and Missouri Rivers? Black bass and pickerel in the Elkhorn? This fish story that dates to 1873 has largely been lost to the annals of time, and how it happened almost defies logic — what are the chances? — but trust us, it is true. For almost a decade some of the best freshwater fishing anywhere in the country was in eastern Nebraska's waterways. What made for an angler's delight were a rainy spell, a railroad trestle collapse between Elkhorn and Waterloo and an aquarium car on a Union Pacific train bound for California. That's right. An aquarium car. Our yarn starts in 1873, when the California Fish Commission chartered a Central Pacific Railroad fruit car to be sent to New England to be fitted as an aquarium. The mission: Stock California's waterways with non-native species. The man in charge: Livingston Stone of the United States Fish Commission. It was front-page news for the San Francisco Examiner, which printed a letter Stone wrote to the fish commission and included this prophetic excerpt: "I think I shall be able to start with a good supply of fishes, but the chances against getting them across the continent alive are enormous. Still, everything will be done that experience and care can dictate and while we will prepare for the worst we will hope for the best." He hadn't counted on a rainy spring in Nebraska. In New England, Stone was collecting his living fish. From his account in a federal fisheries report published in 1876, upward of 60 black bass and 11 walleyes from Lake Champlain, 190 yellow perch and 12 bullheads from the Missisquoi River, 110 catfish from the Raritan River, 20 tautogs (blackfish) and 1,500 fresh-water eels from Martha's Vineyard, 1,000 eastern trout from Charlestown and 162 lobsters and a barrel of oysters from Massachusetts Bay. The black bass, bullheads, catfish and some of the lobsters were "full-grown and heavy with spawn." All went into the aquarium car. It held a 5-ton covered tank that was the width of the car, 32 inches deep and 8 feet long. At the other end were an icebox and "the reserves of sea-water, six large cases of lobsters and a barrel of oysters." Portable tanks were in the center of the car. Four passengers, including Stone, slept on top of the 5-ton tank. At Albany, New York, 40,000 fresh-water eels from the Hudson River were loaded. At Chicago, 20,000 shad and shad eggs and perhaps some salmon were brought on board to stock the Great Salt Lake in Utah. The train went on the U.P. line in Omaha on June 8. Aside from some eels and a few lobsters that had perished, Stone wrote, "everything was promising well." Until dinner time that Sunday afternoon. Stone:"Suddenly there came a terrible crash, and tanks, ice and everything in the car seemed to strike us in every direction. We were, everyone of us, at once wedged in by the heavy weights upon us." A trestle over a flooding slough east of the Elkhorn River, 400 feet long and 12 feet high, had weakened from the soggy conditions. The front of the train, which included a mail car behind the aquarium car and then several passenger cars, tumbled into what the Omaha Republican newspaper called 10 feet of water in a rapid current. The U.P. roadmaster riding in the engine, 35-year-old Michael Carey of Omaha, died in the wreckage. His was the first burial in the newly consecrated Holy Sepulchre Cemetery at 48th and Leavenworth Streets, and the only death from the accident. Stone and the others in the aquarium car swam around the car and climbed on the engine to reach safety. All others on the train survived. "Growing up in Gretna, I remember the old-timers talking about this,'' said Greg Wagner, a longtime spokesman for the Nebraska Game and Parks Commission. "They'd refer to it as 'The Wreck.' " How about the fish in the aquarium car? Stone, in The Omaha Herald the day after the accident, said:"The fish have all been lost in the Elkhorn River, which at the present time (is) very high and muddy, and no doubt, all of the fish soon perished in that water so that even Nebraska will not be benefited by the sudden fish planting." The tautog (blackfish), lobsters and oysters didn't survive. The others apparently thrived, according to these newspaper accounts.  A trestle over a flooding slough east of the Elkhorn River, 400 feet long and 12 feet high, had weakened from the soggy conditions. The crash stocked eastern Nebraska rivers with fish during the late 1800s. At the time:Omaha Republican: "When the fish car went through the trestle work it sunk completely under water, where it toppled over and the fish escaped into the slough and thence to the Elkhorn. At least a million of small fry were then let loose into a Nebraska stream. The river is quite muddy now, so some of them will probably die but the greater portion will live, increase and multiply. "It is not very joyful news to the owners of the fish or to those who may have to pay for them, but it is a big thing for the Elkhorn River, which is thus magnificently stocked free with the finest varieties of fish." Three years later, in 1876:Kansas City Journal: "At Plattsmouth, some fishermen hauled a seine in the Missouri and among the fish taken were a large number of salmon from six to 18 inches long. These fish, it is believed, came from the Elkhorn. … So it will be seen that the accident is proving a benefit to Nebraska and it demonstrates that salmon will flourish in our streams, as muddy as they are." It should be noted that the salmon could have come from stockings by the U.S. Fish Commission along the Missouri from the Floyd River at Sioux City, Iowa, to Council Bluffs in 1875. Isn't there a little wiggle room to every fish story? Four years later, 1877:Nebraska State Journal: "We are reminded of the great washout whereby $20,000 worth of 'fish seed' was spilled into the running waters by the sight of some of those very fish which have been caught by the boys in the river and lakes hereabouts. Black bass … trout, pickerel, pike and salmon, as well as eels, have been captured in sufficient quantities to demonstrate the fact that this whole water course has been well stocked with these beautiful and excellent fish." Omaha Herald: "Now we are beginning to realize on our home fisheries. Yesterday Sheely Bros. received a shipment of salmon taken from the Elkhorn at Waterloo. Our readers will remember that a few years ago … spaun (sic) went into the river. Nice thing, wasn't it?" Even seven years later, 1880:Omaha Daily Herald: "Fishermen are catching large numbers of black bass, pickerel and other choice fish from the (Platte) river near Ashland, the progeny of those spilled into the Elkhorn river a few years ago by an accident to a car filled with live young fish from the Atlantic seaboard." Finally in the early 1880s, the great fishing dried up in Nebraska.How did the hooks come up empty? We don't know for sure. Certainly some of the exotic species fared poorly. Another contributory factor could be this concern of the Nebraska State Journal in 1879: "There are parties who own seines and drag the waters clean of fish at all seasons. Fishing with nets should be stopped at once." Did California ever get its fish? Yes. After the wreck, Stone returned to New England for an immediate retry, this time bringing only shad to California. On the trip west, he asked that the train be stopped at the wreck site so he could bring on 50 gallons of Elkhorn River water for the remainder of the trip to California. A year later, he delivered a carload of the eastern species to California in eight days. His legacy is such that the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service's hatchery in Shasta, California, is named for him. Since then, this story has been largely forgotten. Some details were included in a 1963 publication of the Game and Parks Commission, "A History of Fisheries Resources," by David J. Jones with illustrations by Frank Holub. In Nebraska, the wreck and the subsequent fishing boon spawned the interest to start a private hatchery near Gretna in 1877, so game fish no longer had to be imported, and a state fish commission was created two years later. That agency is now the Game and Parks Commission. Transporting fish nationwide by rail continued until truck and air travel became more feasible and economical after World War II, as explained in a 1947 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service historical booklet. Raquel Espinoza, Union Pacific senior director for corporate communications and media relations, found the booklet in the railroad's archive. She said the Union Pacific Historical Museum in Council Bluffs had no mention of the 1873 wreck in its files. The Fish and Wildlife Service history, interestingly, begins with Stone's shad-only trip — the one after the wreck — and places it a year later in 1874. It said the trip was made in Fish Car No. 2. But after reading this fish tale, you now know what happened to Car No. 1. Trophy Board photos: Nebraskans and their trophiesSee a photo gallery featuring some local hunters' top prizes from across the Midlands.  Name: Cade Atkinson, Gothenburg, Nebraska Species: Mule deer Where: Southwest of Gothenburg Size: 5x5 Noteworthy: It was the 11-year-old's second deer, which he took with the help of his dad, Brent Atkinson. Cade was able to take the buck down with one shot at 130 yards.  Name: Chris Taylor, Fremont. Species: Largemouth bass. Where: Private lake in Fremont. Size: 21 inches. Noteworthy: The 10-year-old caught the Master Angler fish using purple spinner bait.  Name: Tom Boyer, Omaha, with grandfather Jeff Carney Species: Blue catfish Where: Sandpit Lake near Ashland, Nebraska Size: 45 inches Noteworthy: This isn't the first big catfish Tom has caught, but he earned his first Master Angler certificate. In the past, the 7-year-old wasn't able to reel the fish all the way in on his own. This time he did, although he did take three rest breaks.  Name: Dylan Clark, Omaha. Species: Spoonbill. Where: Lake of the Ozarks with grandpa Butch Clark and friend Brian Hinenan. Size: 52 pounds. Noteworthy: This was Dylan's biggest catch ever.  Name: Bob Story, at left, Central City Species: Channel catfish Where: Loup Canal in Platte County Size: 26.5 pounds Noteworthy: The 75-year-old landed the fish with some help from friends. Despite a severe fish kill a few years ago and March flood damage in the upper canal in March, the fishing in the lower half has been good this summer.  Name: Maezlyn Witherbee-Alef, Bennington Species: White crappie Where: Lake near Plattsmouth Size: ¾ of a pound Noteworthy: It was the 4-year-old's first crappie. She is pictured with her grandfather, Mark Witherbee.  Name: Nate Ruffino. Species: Muskie. Where: Eagle Lake Sportsmen's Lodge in Ontario, Canada. Size: 40 pounds, 50 inches. Noteworthy: Ruffino was casting on the dock when a 25-inch northen pike hit his bait. While reaching for his net the muskie came out and grabbed the pike. It took three people to net the fish and hoist him into the boat. Nate was fishing with his father, Tom Ruffino, and friends Frank and Andy Tworek, Ron Schmidt and Frank Mason.  Name: Hunter Redfern, Elkhorn. Species: Cottontail. Where: Stanton, Nebraska. Noteworthy: The 9-year-old was hunting with his dad, John, at his Gram's farm when he shot this cottontail rabbit. It was Hunter's first animal harvested with a .22 rifle.  Name: Claudia Riggert, Pierce, Nebraska. Species: Deer. Where: Pierce County. Size: 4x4. Noteworthy: The 11-year-old killed her first deer from 217 yards with her .243.  Name: L.D. "Spike" Gross, Fremont. Species: King salmon. Where: Lake Michigan out of Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin. Size: 28½ pounds. Noteworthy: The fish was caught on flash bait from the deck of the Top Banana, a charter boat. The captain was Patrick Vesser.  Name: Jay Wiederholt, with children Mara and Max. Species: Largemouth bass. Where: Neighborhood pond in Sedalia, Missouri. Noteworthy: Jay is a dedicated golfer. His brother-in-law, Bob, offered to take him fishing via golf cart. Several bass were caught and released.  Name: Bill Henk, Omaha Species: White-tailed deer Where: North of Loup River in Howard County Size: 11x8 points. Brow tines 9 inches Noteworthy: Henk said this is his biggest trophy. It appeared out of a tree-lined draw just 15 minutes after he got in his stand at 2 p.m. He shot it from 150 yards.  Name: John Beeson, Omaha Species: Deer Where: Otoe County southwest of Palmyra Size: 4x4 Noteworthy: The UNK senior killed the deer with one shot from 80 yards with a Savage .270 rifle. It's the third deer of his hunting career.  Name: Dean Cowles Species: Tiger trout Where: Two Rivers Noteworthy: The 93-year-old has caught virtually all varieties of trout over the years but never the hybrid tiger trout. It was a goal of his before he quit fishing. He caught two that day.  Name: Derek Rutherford, Omaha. Species: Catfish. Where: Private lake near Valley. Size: 16 inches. Noteworthy: After several nibbles and lots of patience, Derek landed the biggest fish he's ever caught. It was released.  Name: Emmett Golda, La Vista Species: Bass Size: 3 pounds Where: Halleck Lake in Papillion Noteworthy: Moments after dropping his line in the water, the 3-year-old needed a little assistance from grandpa Keith Bonner to reel in this fish caught with a bait worm. It was his first time fishing. His parents are Luke and Kay Golda.  Name: Klaus Brotzki, Omaha. Species: Largemouth bass Where: Private lake in north central Missouri. Size: 6 pounds, 9 ounces Noteworthy: It was caught in 12 feet of water using a chartreuse and white chatterbait. It was weighed and released.  Name: Grant Ryan, 10 Species: Blue Catfish Where: Saunders County sandpit lake Size: 44 inches long Noteworthy: The fish qualifies for Nebraska Game and Parks' Master Angler recognition. This is the second big catfish Grant has caught with his grandfather, Jeff Carney. Once the fish was released, he turned to his dad, Ben, and said: "This never gets old!"  Name: Samuel Baumert Hometown: Norfolk Species: 15½-inch crappie Location: Near Schuyler. Note: The 6-year-old caught the Master Angler fish on an outing with his family. He used a minnow as bait.  Name: Bridget White, Springfield, Nebraska Species: Triggerfish Where: Off the coast of Cancun in the Caribbean Size: 6 pounds Noteworthy: Bridget and Phil White caught six trigger fish and one white and one red snapper while out on a fishing charter.  Name: Ben Zupan, Elkhorn Species: Bluegill and crappie Where: Lake Wanahoo Size: Around 10 inches Ben Zupan also was on his first ice fishing outing, a Nebraska Game and Parks Commission event at Lake Wanahoo. Game and Parks provided gear and bait and even drilled the holes. The 16-year-old caught 15 fish, and grandpa Patrick McPherson caught four. "Over the last 12 years I've enjoyed teaching him how to fish,'' McPherson said. "He's become an extremely good fisherman who loves the outdoors and can't wait to go fishing. And, he's a better and smarter fisherman than his grandpa. Don't tell him that."  Name: Jamison Childers, Omaha What: Largemouth bass Where: Douglas County private pond Size: 17 inches It was priceless, Paul Childers said, to see the smile on grandson Jamison's face when he pulled in his prize on the youngster's first ice fishing trip. "Seeing him sitting in his chair and all of a sudden hearing, 'Papa, I got one.' All I did was put a few fingers underneath the pole and he reeled them in,'' Childers said. The 6-year-old caught a 17-inch and a 19-inch bass on a private pond in Douglas County. Childers caught a 21-incher.  Name: Jace Sheppard This past July, the 8-year-old caught a pike at Lake of the Woods in Canada.  Name: Becky Connolly with guide Dean Roy, who is holding the fish. Husband Dan is to the left. Species: Muskellunge Where: Lake of the Woods Size: 47-¼ inches, about 37 pounds Noteworthy: The fish was caught on a jig and nightcrawler while fishing for walleye with a 6-pound line and a light-action rod. It was released unharmed.  Name: Don Paltani and grandson Wyatt, Bellevue Species: Whitetail buck Where: Cass County Size: 5x5 Noteworthy: Paltani said it was a proud moment. Wyatt helped out with everything in taking care of the deer. "It is a moment to not be forgotten," Paltani said. "We look forward to more proud moments like this one when Wyatt comes of age to hunt."  Name: Clay Gathye, Gretna, and grandpa Larry Gathye, Omaha Species: Mule deer Where: Pine Ridge in western Nebraska Size: 2x3 Noteworthy: The 10-year-old shot his first deer on opening day using his grandpa's .308 rifle.  Name: Charlie Loofe, Elkhorn Species: Walleye Where: Buckskin Lake near Newcastle, Nebraska Size: 20 inches Noteworthy: The 10-year old was fishing with grandfather Mike Loofe of Wakefield.  Name: Michael Marcuzzo, Omaha Species: Flathead catfish Where: Omaha park Size: 25 pounds, 39 inches Noteworthy: Marcuzzo was fishing with a friend at a local park when he caught this master angler with a bluegill. The fish was released.  Name: Truman Stickland, Red Oak, Iowa Species: Bluegill Where: Viking Lake in southwest Iowa Size: 10 inches Noteworthy: Truman and brother Bennett caught some small fish, then Truman reeled in this one. Mom wasn't impressed, but Truman insisted he take it home. They then checked with Todd Carrick of the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, who said it was a master angler catch.  Name: Jeff Schindler, Valley Species: Lingcod Where: Homer, Alaska Size: 45 pounds Noteworthy: Jeff was fishing with dad Ron and brothers Brad and Rod. As he was reeling in a rock fish, this monster latched on. The quick-thinking captain gaffed it before it let go. Both fish were landed in the boat.  Name: Jack Taylor, Bellevue Species: Largemouth bass Where: Private pond in Sarpy County Size: More than 3 pounds Noteworthy: He was fishing with his father, Aaron Taylor, and Jerry Lovell.  Name: Doug Mellema, Kansas City, Missouri Species: Largemouth bass Where: Smithville Lake, Missouri Size: 5 pounds Noteworthy: The fish was caught on the second cast of the morning, using a Rapala Fat Rap, firetiger color. It was netted by Doug's father, Warren Mellema of Omaha.  Name: Dean Cowles, Plattsmouth Species: Koi Where: Two Rivers Size: 14 pounds Noteworthy: Dean, 92, was fishing for trout when he caught this koi.  Name: Davis Koile, Valley Species: Bass Where: Valley Size: 21 inches Noteworthy: The 7-year-old used a green pumpkin worm with a chartreuse tip rigged wacky style on a drop shot rig. The fish, which weighed 4 pounds, 3 ounces, was his first master angler bass. This catch made him "want to get even bigger ones."  Name: Andrue Hackendahl, Elkhorn Species: Redear sunfish Where: Lawrence Youngman Lake Size: Just over 10 inches Noteworthy: The 9-year-old thought another little fish was stealing his night crawler. It was released.  Name: Ainsley Anderson, Omaha Species: Walleye Where: Lake Pokegama in Minnesota Size: 29 inches Noteworthy: The 11-year-old used a Silver Wally Diver to catch the 9-pound fish, which was her second master angler walleye.  Name: Hayden Anibal, Bennington Species: Crappie Where: Sandpit lake near Schuyler Size: 16 inches Noteworthy: The 11-year-old used a night crawler to nab her master angler fish.  Name: Emma Anibal, Bennington Species: Largemouth bass Where: Sandpit lake near Schuyler Size: 18 1⁄2 inches Noteworthy: The 12-year-old used a night crawler to catch the bass.  Name: Carter Cushing, Gretna Species: Channel catfish Where: Platte River Size: 20 pounds Noteworthy: The 14-year-old was fishing with his family, including sister Avery. The catfish put up a good fight and was released.  Name: Erik Hultquist, Omaha Species: Brown trout Where: Fraser River, Tabernash, Colorado Size: 22 inches Noteworthy: The 14-year-old was fly-fishing for the first time on a river.  Name: Gary Jacobsen, Omaha Species: King salmon Where: Kenai River in Alaska Size: 50 pounds Noteworthy: He was fishing with son Chris of Tekamah, Rick Beane of Minnesota and Dan and Eric Jensen of Kenai.  Name: Frankie Jordan, Omaha Species: Largemouth bass Where: East Silent Lake, Minnesota Size: 4 1⁄2 pounds, 19 inches  Name: Mitch Stanley, Elkhorn Species: Smallmouth bass Where: Boy Lake, Longville, Minnesota Size: 5-1⁄4 pounds, 21-1⁄2 inches long Noteworthy: Mitch was fishing with his grandfather, Gary Lortz. He caught the master angler fish with a leech. The fish was released.  Name: John Swinarski, Omaha Species: Whitetail deer Where: Sarpy County Size: 7-pointer Noteworthy: Swinarski wants to thank the farmers and landowners who allow hunters on their land. "Really appreciate it,'' he said. "We are always looking for more hunting land.''  Names: Cooper and R.J. Hladik, Sedalia, Missouri Species: Largemouth bass Where: neighborhood pond in Sedalia Noteworthy: The boys also caught dozens of scrappy bluegills that were about 10 inches. They used hot dog bites and worms to catch green sunfish, too. All were released.  Couy, Reece and Nick French with a 113 1/4 pound blue catfish. It was 5-foot-1 inches tall with a girth of 3 feet 11 inches.  Name: Doug Finnicum, Omaha Species: Largemouth bass Where: Douglas County private lake Size: 4 to 6 pounds Noteworthy: It was his largest bass from this lake.  Name: John Schulte, Omaha Species: Pheasant Where: Public land near Columbus Noteworthy: The 13-year-old used his 20 gauge shotgun to kill his first rooster during the youth pheasant opener. He was hunting with springers Ruby, who flushed the wild rooster out of a plum thicket, and Camo, who retrieved it.  Drake Clements got a 16-point buck on the first day of the firearm deer season. It was the 11-year-old's first buck.  Name: Kevin Marr, Omaha Species: Wiper Where: Lake Manawa Size: About 8 pounds, 3⁄4 inches Noteworthy: Marr fishes at the lake every Monday. This time it was cold and windy, but he persevered on the fourth cast. It took about 17 minutes to bring the fish in.  Name: Michael Bebout Species:Whitetail deer Where: Johnson County by Sterling on his grandmother's land. Size: 5x5 Noteworthy:Michael shot this 3 1/2 year old deer at 160 yards with a Browning .270. It is his biggest buck so far. This buck was so well hidden in the timber that, after shot, they walked within 2 foot of the deer and couldn't see him. Michael found him. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "beautiful fish tanks" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment