This Nest of Dangers: Jim Gibbs — Historian brought sea stories to life - Chinook Observer

This Nest of Dangers: Jim Gibbs — Historian brought sea stories to life - Chinook Observer |

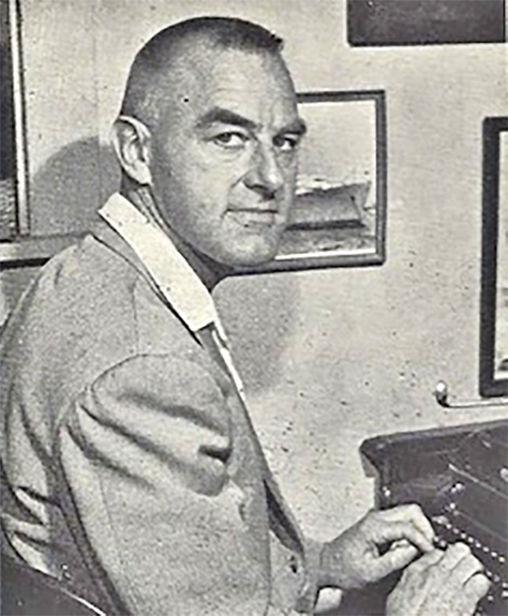

| This Nest of Dangers: Jim Gibbs — Historian brought sea stories to life - Chinook Observer Posted: 18 Jun 2020 08:43 AM PDT  The other day, as I began work on an essay about the first Columbia River Lightship, No. 50, I checked something in Jim Gibbs's book, "Pacific Graveyard." That set me to thinking about Gibbs's career and work. "Pacific Graveyard" was the chatty, best-selling, detailed telling of the maritime disasters out our back door. Scholars grumble that the book isn't perfect — it lacks references, tells some iffy stories — forgetting that it is volunteer history, the result of the writer's vital interest, rather than ordinary academic requirement, and that it was the first of its kind for the West Coast. Over the course of his life, Gibbs published more than 20 books on regional maritime subjects, served for 20 years as editor of Seattle's Marine Digest, co-founded the Puget Sound Maritime Historical Society, and, toward the end of his long life, built and operated a Coast-Guard-approved lighthouse on the mid-coast of Oregon. During World War II, Gibbs served with the Coast Guard and was, for a year, a keeper stationed at Tillamook Rock Lighthouse, out there in the ocean, a mile and a half from the Oregon shore between Seaside and Cannon Beach, where the breakers hammered and over-topped the Rock. He was born in Seattle in 1922; the family lived on Queen Anne Hill overlooking Seattle's busy waterfront. From the window of his attic bedroom young Jim watched the activity, ships arriving and departing, being unloaded and loaded. Every so often he walked down to the wharves to talk to the sailors. From the Yachats (Oregon) Gazette of May 31, 2013, in an interview with Gibbs's son-in-law and daughter, we read, "As a little kid, [Gibbs] started recording what ships came in, what ships left, who was the captain — stuff like that. … [B]ack in those days you could walk on down and talk to [the mariners]. He got to know them, and then he read stuff on them. From the time he was a young kid to the time he died, even though his mind was getting … foggy, the one thing he always knew, whenever somebody was sitting here interviewing or questioning him: […] ship tonnage, where it was going, who was its captain, what its cargo was: he knew everything." James A. Gibbs Jr. enlisted in the U.S. Coast Guard during World War II. Decades later, a story about those days surfaced in an opinion piece in Salem's Statesman Journal. "I have read a good book," wrote the editor, "on the history of Oregon. It is 'Oregon's Salty Coast' by Jim Gibbs. He was on beach patrol in the Coast Guard in World War II, walking the beach north of Pacific City. One day, he, his buddy and dog were patrolling and the dog fell over a cliff. They radioed for help, not realizing that they were setting off an invasion alarm. Soon, a sizable military force showed up in the dark, expecting to meet the Japanese. Gibbs and his buddy thought the rescue group was Japanese. The upshot was that the dog was kicked out of the Coast Guard for chasing birds, and the two men were busted in rank." Perhaps that tale was what Gibbs had in mind when he told another Statesman-Journal writer about his move to serve on Tillamook Rock. "'But I was a screw-up, a maverick, and I got into trouble,' he said. 'The Coast Guard exiled me to Tillamook Rock Lighthouse, the Alcatraz of Coast Guard stations. At first I hated it — three weeks on and three weeks off. But then it began to grow on me. I discovered I liked being alone.'" The book he later wrote about those days, "Tillamook Light," published by Portland's Binford & Mort in 1979, makes for original reading. One early experience he recounts is "bombing" a huge whale engaged in scratching the barnacles off his hide by rubbing against the Rock. Gibbs reported the whale's presence to the other three keepers but they weren't interested. Pull Quote

"So I decided to get a little action out of the critter," wrote Gibbs. "Finding a large 50-pound hunk of rock a previous storm had torn loose, I crept back over the railing to the target site. … Zeroing in, I braced myself …Down plummeted the missile … I had only meant to scare the mammoth mammal, but the bomb … struck it on the back of the head — a direct hit. "With the suddenness of a lightning flash, a massive forked-tail became airborne. Like a great juggernaut, thrashing, writhing, the leviathan broke the surface and charged the basaltic mass [Tillamook Rock], ramming its snout with a sickening thud. I thought the entire rock would be decapitated, when suddenly the whale disappeared into the depths. The ocean was a foamy mass, punctured by whirlpools and masses of effervescent bubbles. "When the monster surfaced a second time, the jaw was wide open. Giant fountains of water erupted from its blowhole as the barnacle-covered back arched above the boiling maelstrom. As if searching out its foe, the whale's desperate antics continued for nearly 15 minutes. I could only imagine the fury and anger of that swimming tornado. Glad to be well out of its range and preferring not to be a second Jonah, I watched with amazement. Never relaxing, the mammal propelled itself at furious speeds. Each time the frenzied battering ram passed below me, its proportions seemed to increase in size. … "The whale, exhausted but still furious, finally gave up and vanished into the deep …" Shades of "Moby-Dick" … In those early days on the isolated lighthouse with its crew of four, Gibbs found the principal problem was melancholy. The fast pace of mainland life was no part of isolated lighthouse life. Absorbed by historyOne time, after he had done everything he knew to perfectly polish the huge many-lensed first order Fresnel light and was wondering how else to occupy his time, he discovered the attic library, an "… ancient collection of literature. The sagging shelves labored with books and periodicals from bygone years. Apparently none of the collection had been discarded since the incarceration of the first lighthouse keeper. Every subject imaginable ['Tom Swift' included] was contained in dust-covered volumes donated down through the years by sympathetic seashore humanitarians." "In one corner," Gibbs wrote, "was a neat stack of old lighthouse records and logbooks … As I examined the contents of their moldy pages, I soon became absorbed and found myself reading far into the night. Those early excerpts told of the staggering toll of shipwreck[s] on and around the mouth of the Columbia River, a primary factor in the decision to construct the lighthouse. In early years that disreputable river-bar approach had been the bane of mariners." Gibbs began to read about the periodic violence of the weather. "During a gale in January of 1883, fragments torn loose from the rock by treacherous seas, knocked several large holes in the iron roof of the foghorn house. In December of 1886, a mass of concrete filling, weighing half a ton, was ripped loose by rampaging seas and thrown … 100 feet above the ocean. … In the severest storm of December, 1887, the keepers reported that seas continuously broke over the tower, 134 feet above the sea, smashing the lantern panes and flooding the interior rooms. Dec. 9, 1894, saw great seas that breached the entire station, destroying thirteen lantern panes, chipping the lens, and tearing off weighty fragments of rock that punctured the roof of the dwelling and foghorn house, pouring in gallons of salt water and quantities of debris. …" He added, foretelling the Coast Guard's retirement of this particular lighthouse in 1957, "The alarming cost of maintenance, repair and supply made the rock the most expensive item on the list of United States lighthouses." Then Gibbs spoke of a gale in October 1934. "Tremendous seas submerged the entire station during that blow … small fish and seaweed were deposited in the lantern room. … The keepers worked up to their waists in saltwater as the seas pummeled the tower, sending torrents of water down the circular stairs to flood the inside of the lighthouse." "The courage of the keepers under extreme duress was outstanding. Nobody slept; it was work 24 hours around the clock." Glimpse into the past"The hour was now late. Time had passed me by as I eagerly read the old lighthouse records," Gibbs wrote, "but on leaving that attic library I … had gained a new cross-section into life in a lighthouse … Though the life might have seemed repetitious to the outside world, to me it was beginning to assume a reality like a story that never grows old. True, I had hated my existence [on the Rock] for many weeks, but things suddenly took on a glow. The sea in all its moods became fascinating — the storms, the birds, the strange creatures of the deep. … [As a young man] little did I realize that fate would give me the role of a lighthouse keeper, not in a peaceful spot such as one might see from the deck of a pudgy [Puget Sound] ferryboat crossing a protected inlet, but on a notorious crag … a weather-beaten sentinel given to the ways of the sea. … From its portals spread the oldest and greatest of oceans, for almost half of the water of the world is in the vast Pacific, endless, dangerous, and furrowed by steep trenches." He continued, "Having hurdled the first obstacle in conquering the pangs of isolation, there was still another problem … namely, transformation of mind over matter. True, the eerie light and the vexatious foghorn were a malediction in themselves, and the varied assortment of characters who inhabited lighthouses were without precedent, but through it all I at last gained a feeling of responsibility apart from my surroundings — that of keeping the light burning for struggling seafarers." And he described his first-person experience with what was probably a hurricane: "All that night it blew terribly hard, raising angered and lunging seas such as I could not remember. During my graveyard watch … the glass [barometer] was low, and though I knew greater hurricanes had hit the rock, to me it was a sight to behold. … The lighthouse groaned like a live creature in the mire of doom. The seas slammed against it with such shocks that I thought it would be torn from its roots and tossed into the ocean. Tons of water swept over the top of the dwelling … I watched the fury of the gale from behind bolted doors. … "When I awakened the following morning, the gale had not abated an iota … looking out the porthole of my room gave me the sensation of being in a submarine, ten fathoms down. … The structure trembled as the breakers discharged their violence at a height equal to a ten-story building. … This was my first genuine initiation to a full gale aboard the rock, and you haven't really lived until spending a night at the lighthouse under such conditions. You didn't dare step outside for fear of your life. Seas were not only breaching the rock but were sending green brine entirely over the lantern. … "I went over to check the glass again and saw something I had never before seen. The [barometric] pressure was so great when a massive wall of water passed over the structure that the barometer needle actually dropped from 28.50 to 27 inches of pressure for a brief second and then shot back to the original position." "Though the storm's fury was frightening, it was also exciting." "Despite my early hatred of the rock, I had gradually grown very fond of it and had learned a whole new side to life, that of being in a lonely place and yet finding fulfillment in the natural wonders of God's world. Where else could you be on a small islet with a perfect 360-degree view of the ocean in all of its varied moods, a place with a grandstand seat for the most beautiful sunrises and sunsets … Where else could you better see the endless string of sea birds flying south in the fall or watch the vast aquarium of mammals and fish cavorting about." Lifetime's vocationIs it any wonder that Jim Gibbs, after spending one year's duty on Tillamook Rock, spent the rest of his life writing about the sea, shipwrecks, and lighthouses? He had been perfectly prepared to tell the rest of us about the subject. His foundational book was "Pacific Graveyard," first published in 1950. In a postscript to his writing career, Gibbs told an anecdote during a 1993 interview with the Statesman-Journal: "His writing career started when he was a banished coastguardsman on Tillamook Rock's lighthouse in World War II. He wrote a story about his life as a lighthouse [keeper], and sent it to The Oregonian newspaper. 'One day the tender [ship] came out, and our cargo was sent up to us in a sling. There was a letter from The Oregonian on top of the mail. I got a check for $25 for the story,' he said. 'I then decided to be a writer, but after 1,000 rejection slips I had my doubts. I remembered my English teach in high school. She said, "If you ever write anything, it will be over my dead body!" She thought I was a terrible writer.'" Gibbs died in 2010 at his home, Cleft of the Rock Lighthouse, in Yachats, Oregon, at the age of 88. |

| You are subscribed to email updates from "monster aquarium fish" - Google News. To stop receiving these emails, you may unsubscribe now. | Email delivery powered by Google |

| Google, 1600 Amphitheatre Parkway, Mountain View, CA 94043, United States | |

Comments

Post a Comment